Petersfield beekeepers are blessed by living in an area of very varied forage. Situated at the western end of the Weald where the North and South Downs meet, soil types and landscape vary from alkaline to acid, river valley and meadow to wooded hillsides, heath, downs and agricultural land. Settled since prehistoric times and at the junction of two major travel routes, man has also had an impact on the plants growing in our area.

Plants introduced and cultivated by man are important sources of nectar and pollen outside the flowering times of native species. On warm sunny days in winter bees will visit gorse flowering beside the A3 and M27 and winter flowering shrubs and herbaceous plants flowering in our gardens. A pollen guide can be found here

Forage of the Week 30th August 2021:The Bistort family (amplexicaulis) by Anne-Chantal

The Bistort Family is a group of plants that pollinators really appreciate at this time of the year:

The Bistort Family has two distinctive groups of plants, the bistorts proper and the docks and sorrels.

Above are some photos of Bistorts which have papery whitish sheaths at the base of their leaves and small five-petalled flowers. The name bistorta means twice twisted and refers to the shape of the root stock.

Redshank or Persicaria is a common weed with straggly reddish stems; its leaves often have a dark spot and its flowers may be pink or white.

Here are a couple of examples of the 40 or so cultivated ones:

Persicaria amplexcaulis or red bistort is a tall, shade loving perennial much appreciated by bees.

Persicaria bistort is a short, pink flowered perennial forming good ground cover.

Your submissions (including from other associations) would be most welcome to:

.

Forage of the Week 15th August 2021 by Ali Holingbery

Himalayan Balsam is a plant that divides opinion. It is a plant that provides a plentiful supply of forage towards the end of the British summer season which is loved by many of our pollinators; it is also an invasive plant that spreads voraciously and successfully competes with native plant species for space, light, nutrients and pollinators.

Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera) is a native plant of the Himalayas in Pakistan, India, and western Nepa – it is also known as Indian Balsam, Jumping Jack and Kiss-me-on-the-mountain. A relative of the Busy Lizzie, it was introduced to the UK in 1839 by Victorian plant hunters and has since become naturalised where it is found widely on riverbanks, wasteland and damp ground. It has spread rapidly in the last 50 years and the plant tolerates low levels of sun growing between two to three meters tall and forming dense stands. Himalayan Balsam is an annual which produces pinky-purple bonnet-shaped flowers from July to October and nectar which is much sweeter than a lot of our native plants. Explosive green hanging seed pods contain up to 800 seeds and these seeds are thrown up to seven meters away and are transported further afield by water. The seeds have a relatively short viable period of two to three years. Himalayan Basalm has a shallow-rooted root system which can further destabilise colonised riverbanks and cuttings.

Control of the Himalayan Balsam is best done by “Balsam Bashing” where the plants are removed repeatedly from an area before they flower and set seed. Other controls include chemical spraying but both physical removal and chemical spraying are often ineffective in control due to the inaccessible areas where the balsam grows. In 2015 the CABI found a highly selective rust fungus Puccinia komarovii var. glanduliferae to be effective in the control of the plant in the UK. The fungus became the first fungal agent to be used as a classical biological control agent against a weed in Europe. The rust has been released at over 50 sites in the UK and, at sites where the plants are fully susceptible to the strain of rust, the rust is performing well including surviving the UK winters and establishing populations the next year. It has been identified that not all populations of Himalayan balsam in the UK are susceptible to the two strains of fungus held by the CABI and additional strains of rust need to be identified. From molecular studies it is now understood that Himalayan balsam had been introduced into the British Isles on more than one occasion, from multiple locations. Love it or hate it, the Himalayan Balsam will be around in the UK for many years to come.

Your submissions (including from other associations) would be most welcome to:

.

Forage of the Week 25th July 2021 by Chris Clark – Part 3

After a short interlude (Bee Basics assessment etc), here is the third and final in the series of mindfulness forages.

Astrantia major, ‘Ruby Cloud’, never fails to disappoint and is a great addition to a patio or garden.

For a fuller description of astrantia see the previous submission for 21st July 2020. The beetles had something more than mindfulness on their minds!

I hope you have enjoyed these.

We will now be reverting to the ‘normal’ forage.

Your submissions (including from other associations) would be most welcome to:

Looking lovely…”Our friend giving my phlox a late Chelsea-Chop”.

.

Forage of the Week 5th July 2021 by Chris Clark

Chris is doing a series of ‘mindfulness – forages’ in three parts:

This, the second in the series of ‘mindfulness – forages’, is of wild foxgloves (Digitalis purpurea) in the woodland by my garden.

NB For a fuller description see previous forage submission 28th June, 2020.

The magnificent flowers and foraging insects were illuminated against a ‘dark-field’ giving heightened contrast by the west light.

Sit back and enjoy..!

@Our friend going home after a quick forage@…

.

Forage of the Week 28th June 2021 by Chris Clark

Chris is doing a series of ‘mindfulness – forages’ in three parts:

The potential health benefits of practicing mindfulness are well documented. We all practice it knowingly or unknowingly on a daily basis.

I thought that I would try this as applied to forage. I hope you enjoy them. Let me know in the comments section what you think…

The first is my favourite geranium (also voted RHS’s plant of the centenary at the 100th Chelsea Flower Show) Geranium Rozanne.

NB For a fuller description of geraniums see previous forage submission 18th May, 2020.

This herbaceous perennial grows on the corner of my driveway and never fails to delight me and a multitude of pollinating insects. It helps when viewing to have the volume turned up. The first section was taken in the morning when the flowers are fresh and the later against the evening light to heighten the silhouettes of the flowers and insects.

Unfortunately, insects weren’t the only ones to be foraging.

Forage of the Week 21st June 2021 by Matthew Evans

Last year I harvested my first honey from my Bees with a distinctive but not unpleasant flavour I could not put my finger on until my wife identified it correctly, Chestnut.

It should have been obvious to me as my new hive was in the lee of a 50ft young chestnut tree.

The Chestnut appears to come into leaf quite late and the flowers then follow which only now are emerging, our tree bears a nut most years of a size suitable for roasting.

Castanea sativa, the sweet chestnut, Spanish chestnut or just chestnut, is a species of tree in the family Fagaceae, native to Southern Europe and Asia Minor, and widely cultivated throughout the temperate world. A substantial, long-lived deciduous tree, it produces an edible seed, the chestnut, which has been used in cooking since ancient times.

The flowers of both sexes are borne in 10–20 cm (4–8 in) long, upright catkins, the male flowers in the upper part and female flowers in the lower part. In the UK, they appear in late June to July, and by autumn, the female flowers develop into spiny cupules containing 3-7 brownish nuts that are shed during October. The female flowers eventually form a spiky sheath that deters predators from the seed. Chestnut flowers are not self-compatible, meaning that the plant cannot pollinate itself, making cross-pollination necessary.

Hence the importance of our Bees, who are attracted to the mass of the strong-smelling flowers.

Some cultivars only produce one large seed per cupule, while others produce up to three seeds. The nut itself is composed of two skins: an external, shiny brown part, and an internal skin adhering to the fruit. Inside, there is an edible, creamy-white part developed from the cotyledon.

.

Forage of the Week 14th June 2021 by Pippa Barker

Bee forage

The second, over in a couple of weeks is an untidy, gangly 10m tall with flowers that fall as soon as pollinated, creating a pale green blanket over everything beneath.

Forage of the Week 7th June 2021 by our newest contributor Emily Scott : Gorse (Ulex)

The Gorse of True Love

Gorse (Ulex) is a symbol of love and fertility and there is an old saying that goes, “when the gorse is out of bloom, kissing is out of season”.

But you will be delighted to hear that it is usually in bloom somewhere!

For the first six months of the year, common gorse (Ulex Europaeus) produces yellow flowers, followed by its close relatives Western Gorse (Ulex Gallii) and Dwarf Furze (Ulex Minor), which can produce flowers for the remainder of the year.

Gorse, also known as furze or whin, is a genus of flowering plants in the family Fabaceae and a sweet scented, yellow flowered, spiny evergreen shrub. The fruit is a dark purplish-brown pod containing two to three small shiny hard seeds, which are ejected when the pod splits open in hot weather. The genus comprises about twenty species of thorny evergreen shrubs in the subfamily Faboideae of the pea family Fabaceae. The species are native to parts of western Europe and northwest Africa, with the majority of species in Iberia.

The most widely familiar species is common gorse, the only species native to much of western Europe, where it grows in all kinds of habitats, from heaths and coastal grasslands, to towns and gardens. It does particularly love a sunny site (don’t we all), usually on dry, sandy soils. It is also the largest species, reaching 2–3 metres in height; Western Gorse can grow to 8–16 inches and is characteristic of highly exposed Atlantic coastal heathland and montane habitats. In the eastern part of Great Britain, dwarf furze replaces western gorse, growing to around 12 inches in height. Like other members of the pea family, Gorse has nitrogen-fixing bacteria on its roots, so it can live in areas of poor soil quality.

Compact gorse is ideal for a range of nesting heathland, downland and farmland birds, including the Dartford warbler, Stonechat, Linnet and Yellowhammer. The dense structure also provides important refuge for these birds in harsh weather and is essential for the survival of Dartford warblers in winter.

With the arrival of spring, bumble bee queens gradually wake up from hibernation to start a colony on their own. The success of a new bumble bee nest, depends on the queen finding food quickly to have the strength to build a nest and lay eggs. Gorse’s bright yellow, coconut-perfumed flowers produce little nectar, but its early spring blooms can be a life saver to these queens; and to honeybees as well, who have a hard time finding food at this time of the year. Look out for orange/brown pollen loads.

If you can, it is worth watching the honeybees working the Gorse, because the flower is specially designed to make best use of the bees for pollination. The Gorse flowers each have a keel (lower part) and a banner (upper part). The banner is a brightly coloured flag to lure insects. The keel is the boat shaped lower part which offers itself as an insect landing pad. The first bee to land on a freshly opened flower triggers the keel to burst apart, releasing the spring-loaded reproductive paraphernalia, which shoots forth like a boxing glove on a spring. The unsuspecting bee is hoisted into the air and a bunch of stamens, like a paintbrush, dusts its abdomen with pollen. At the same time, the style (female bit), jabs the bee in the belly and picks up gorse pollen from a previous floral heist.

A few Gorse facts:

- The flowers have a distinctive coconut smell, however how strong they smell varies greatly from person to person.

- Before the Industrial Revolution, Gorse was used as fuel for firing bread ovens and kilns

- It was also used as a fodder for livestock

- Gorse was bound to make floor and chimney brushes

- It was used as a colourant for painting Easter eggs

- Gorse was voted as the county flower of Belfast

Gorse has also traditionally been used in country wine making and to flavour Irish whiskey and beer. Several British contemporary and classic style gins use Gorse petals as a botanical.

You could make a cordial with Gorse:

- 1 pint Gorse flowers

- 1 pint water

- 250g sugar

- 1 orange juice and zest

- 1 lemon (unwaxed) juice and zest

Make a gorse-flavoured syrup by putting your gorse flowers in a saucepan, along with the water, sugar, orange and lemon juice and zest. Bring to the boil, stirring continuously. When all the sugar has dissolved, remove from the heat and leave the flowers to steep. When cooled, sieve the syrup to remove the flowers.

Or, you can make a gorse-infused spirit, by simply infusing a handful of fresh gorse flowers in vodka or white rum for a couple of days, strain and add a little sugar to taste. Cheers!

Forage of the Week 31st May 2021: apple Malus domestica and hawthorn Crataegus by Chris Clark

Apple Blossom Photos

Hawthorn Photos

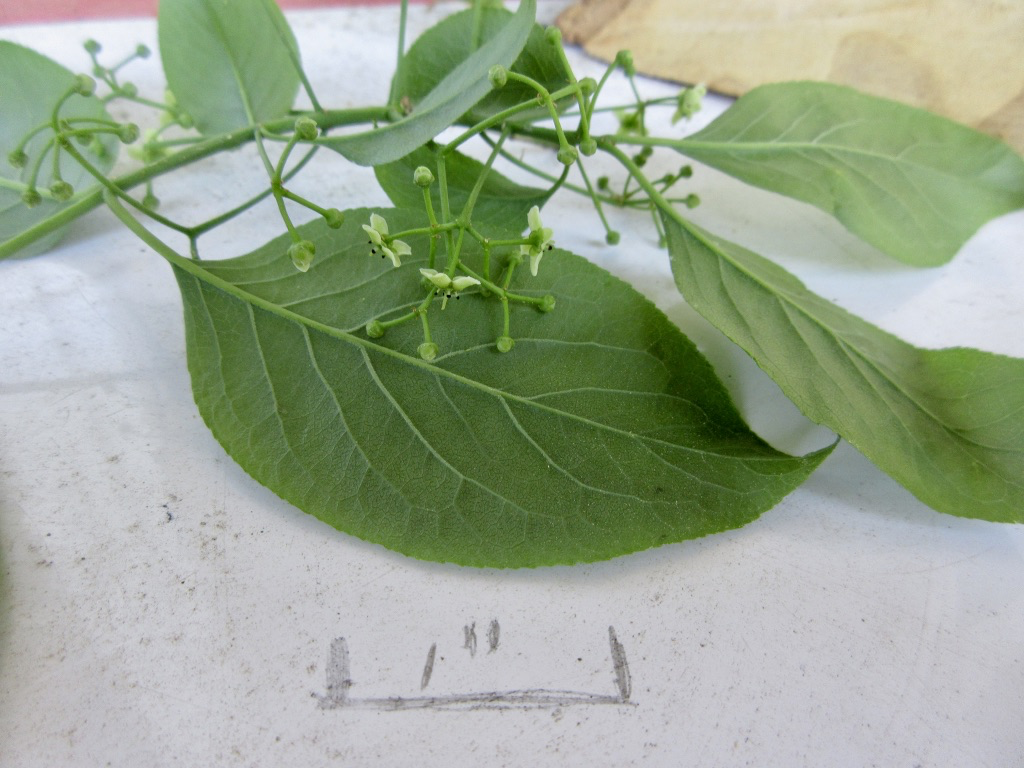

Forage of the Week 24th May, 2021: Dandelion.Taraxacum officinale

Solitary Bees

Although the dandelion is commonly thought of as a weed, it is one of the most useful of wild plants for bees and is a major honey plant for beekeepers. It occurs everywhere and is regularly visited for nectar and pollen. It is found in the flower almost throughout the year, but flower s most freely early in the season, before the appearance of fruit blossom, when it is most valuable to the beekeeper, especially for brood rearing. It occurs freely in pasture, particularly in chalk districts, where fields may be sheets of yellow at flowering time. Dandelion honey varies in density and may be deep or pale yellow in colour. It soon crystallises, doing so with a coarse grain. The flavour is strong.

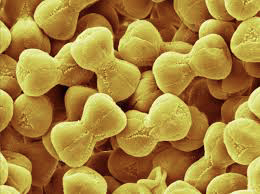

The pollen of the dandelion is golden yellow but may appear as deep orange in bees pollen baskets. It is somewhat oily, and the honeybee wax comb built when dandelion is being freely worked is a distinctive light yellow colour. The individual pollen grain is large and spiny and is very prevalent in English honey.

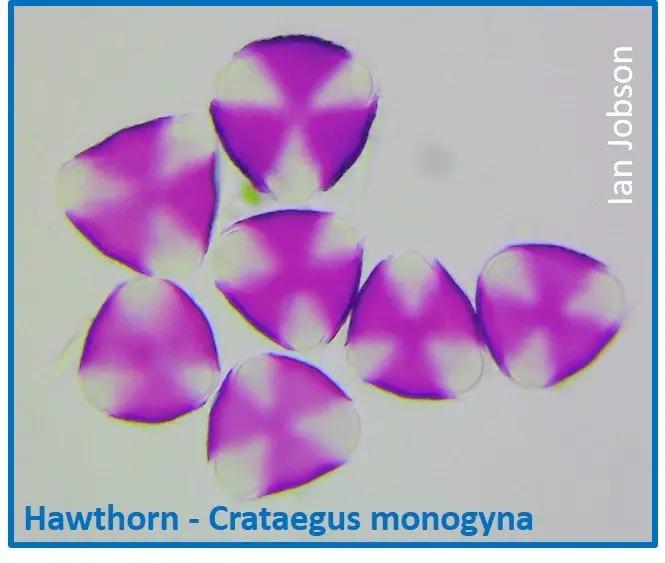

Forage of the Week 17th May, 2021: Cotoneasters

Here is the second submission for Forage of the Week from Paul Matson – newly joined member, Team Clover…

Cotoneasters can be deciduous or evergreen shrubs or small trees, with simple, entire leaves and clusters of small white or pink flowers in spring and summer, followed by showy red, purple or black berries.

The example shown is a cotoneaster horizontalis which is also known as rockspray or wallspray it has a spreading habit and can cover over 2m as it does on the front of my house. It’s origins are from Western China and it is listed in schedule 9 of the UK countryside and wildlife act as an invasive non-native species, although this does not prevent it from being commercially sold.

It is currently covered in tiny small white flowers which obviously have a strong nectar flow and are adored by honey bees, bumble bee species and many other insects.

Forage of the Week 10th May, 2021: Forget-me-not

Here is the first submission of Forage of the Week for this season from ‘Team Clover’s Leader’ – Anne Chantal Ballard.

This is our first example of common, abundant forage for our bees. Chris’s photographs also show how beautiful it looks in the garden. The flowers can vary in colour and additionally, often turn from blue to pink as they are pollinated.

Here are a few facts:

Myosotis (from the Greek: μυοσωτίς “mouse’s ear”, after the leaf) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Boraginaceae.

In the northern hemisphere, they are commonly called forget-me-nots or scorpion grasses. The common name “forget-me-not” was borrowed from the German Vergissmeinnicht, and first used in English in 1398 AD via King Henry IV. Similar names and variations are found in many languages. Myosotis alpestris is the state flower of Alaska and Dalsland Sweden.

Myosotis have 5-merous actinomorphic flowers with 5 sepals and petals. Flowers are typically 1 cm diameter (or less), flat, and blue, pink, white or yellow with yellow centres, growing on scorpioid cymes. They may be annual or perennial with alternate leaves. They typically flower in spring or soon after snow-melt in alpine ecosystems. Their root systems are generally diffuse.

Their seeds are found in small, tulip-shaped pods along the stem to the flower. The pods attach to clothing when brushed against and eventually fall off, leaving the small seed within the pod to germinate elsewhere. Seeds can be collected by putting a piece of paper under the stems and shaking the seed pods and some seeds will fall out.

The pollen grains are very small and the load is yellow.

21st October 2020 – Chris Clark

Ivy, Hedera helix, is a worthy candidate for such a lofty position in the forage season as it is one of the last significant sources of pollen and nectar for insects. Unfortunately considered by many as a nuisance, I have come to view it with different eyes since starting beekeeping. It is an evergreen, woody climber which can grow to a height of 30m. The flowers only form on mature plants of over 20 years old appearing as yellowish green dome-shaped clusters known as umbels. Interestingly the leaf shape changes with the age of the plant from lobed to heart shaped with maturity. The berries have a high fat content and are a nutritious food resource for birds.

Useful links:

Ivy bee – The wildlife Trust

https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/invertebrates/bees-and-wasps/ivy-bee

Chris Clark

7th September 2020 – Anne Chantal Ballard & Chris Clark (Photos)

The cardoon Cynara cardunculus also called artichoke thistle is a thistle in the sunflower family according to Wikipedia. It occurs naturally but has lots of cultivated forms including the globe artichoke. Both grow really easily around here and pollinators love them.

They are beautiful, structural plants but do need staking and if anyone would like some, let me know as I need to dig some out this Autumn!

Anne Chantal .

Chris Clark

17th August 2020

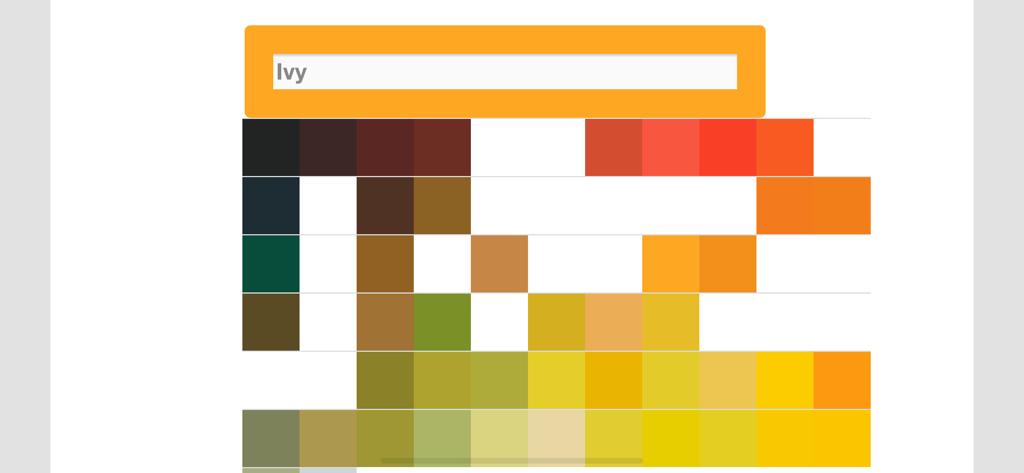

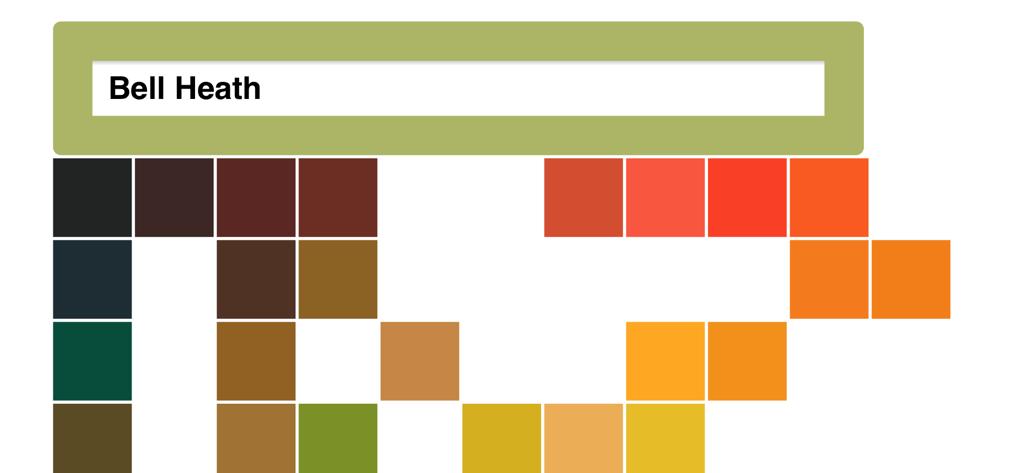

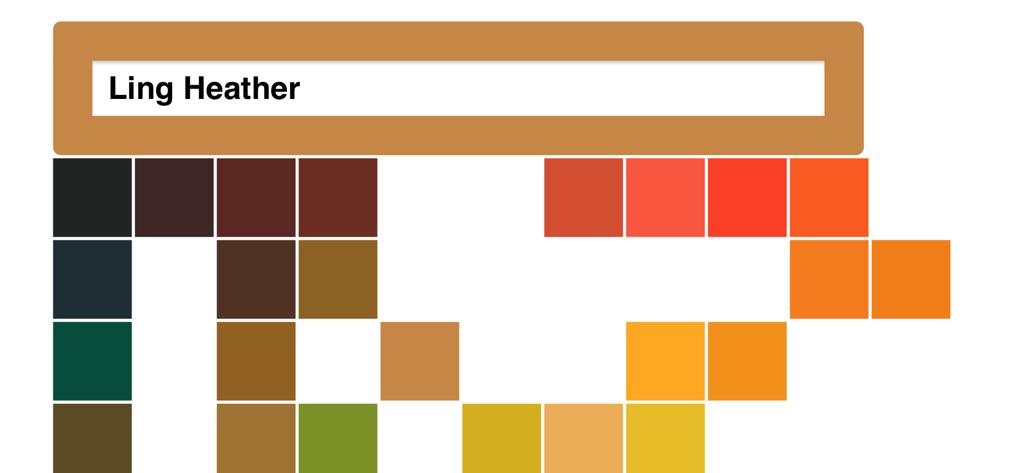

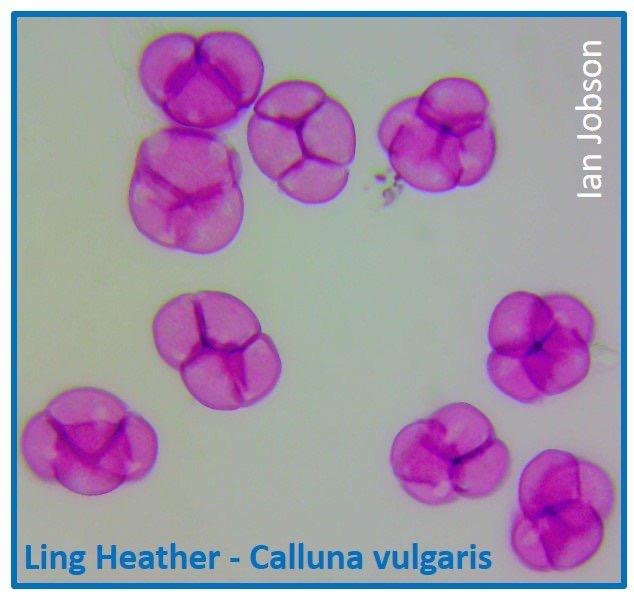

The photographs of heathers below are taken from heathland approx one mile away from Chris’ garden. Heather is an important late source of nectar and pollen for honeybees and its honey is quite special.

Below are some useful links if you would like to read further on heather/honey:

https://www.honeytraveler.com/single-flower-honey/heather-honey/

www.northumbrianbees.co.uk/pollen_gallery/ling-heather-calluna-vulgaris/

https://terryjameswalker.wordpress.com/2014/08/21/difference-between-heather-ling-bell-cross-leaved/

Chris Clark

7th August 2020

Anne Chantal Ballard provides a little info about the Marsh Mallow; the first 3 and last photos.

Marshmallow or Althaea officinalis belongs to the large family of the Malvaceae along with common mallow, white musk mallow, cotton, okra and hibiscus.

Photos 4 and 5, lavateria, 6 and 7, mallow, 8, 9 and 10. All are insect-pollinated and frequented by bees.

High Mallow is a host plant for Painted Lady butterflies (Vanessa cardui). The Painted Lady butterflies lay their eggs on this plant and enjoy its nectar and large leaves, which give them food and protection.

The French word for mallow is ‘mauve’, which is where we get the word for the colour mauve from.

Many are used in herbal medicine. Mallow flower contains a mucous-like substance that protects and soothes the throat and mouth. Marshmallow has traditionally been used by beekeepers to calm bee stings (not a replacement for more modern treatments!).

All the beautiful photos were taken by Chris.

Tuesday 21st July 2020

This week’s forage of the week is Astrantia major which resides in Chris Clark’s garden – The great masterwort, a clump-forming herbaceous perennial, consisting of compact umbels of tiny flowers surrounded by a rosette of showy bracts.

It provides good value for money as the flowering period extends from June till September with a distinctive scent.

Astrantia major is mainly pollinated by beetles but there’s a huge variety of insects that love it. On this subject, there was a lot of love going on by the common soldier beetle (AKA the hogweed bonking beetle) as shown in the pictures. My camera lens was steaming up as there were about 100 pairs mating on different flowers!

Chris Clark

Sunday 12th July 2020

This week’s Forage of the Week is The Bramble – Rubus fruticosus as nominated by Ali Hollingbery

The Bramble, or common blackberry, Rubus fruticosus, is a common prickly shrub that grows enthusiastically in all parts of England, including the hedgerow that surrounds the field where my apiary sits. Best known for its sweet dark fruit, “blackberrying” is a common activity in late summer and autumn. During late June, July and August the blossom provide valuable nectar and pollen for our honeybees and other pollinators. The emergence of the white to pale pink pentamerous flowers often heralds the end of the dreaded, “June Gap” in bee-keeping circles – the time of year when spring flowers are over and the main flow of nectar has yet to start.

The Bramble is a member of the rose family which includes flowering roses, cherries, apples, plums, pears, crabapples and hawthorns. Like the rest of the rose family, Brambles are heavy producers of nectar and pollen and the pollen of the Bramble that appears in our hives at this time of year is a pale-grey buff colour, looking almost moldy or sludgy in the cells. Thankfully, the nectar produces a beautiful clear to amber honey.

In a strict botanical sense, blackberry is not a berry but an aggregate fruit made up of tiny ‘drupelets’. There are over 330 species of bramble in the UK and this helps explain why not all blackberries taste the same. Humans have been eating blackberries for thousands of years as blackberry seeds are often found in the human waste unearthed at archaeological digs. Blackberries are now classified among the antioxidant ‘superfoods’ and contain a rich source of Vitamin C, A, Omega-3, Potassium, and Calcium. As well as the famous blackberry and apple pie, parts of the bramble have traditionally been used to make teas and tinctures and to treat a wide range of ailments including burns, dysentery, skin conditions, and sore throats. Brambles are also a useful tool in forensic botany due to their prevalence of growing on fallow or waste ground and their rhythmic growth pattern. They are commonly used to establish how long human remains have been at a crime scene.

Brambles have a long association with folklore and common names include bumblekites, bounty thorn, skaldberry, blackbutters, blackbides, gatterberry and the prickle-thorn. Traditionally, to harm a bramble bush is forbidden as it belongs to the faerie folk and the first berries of the season must be left for them. If not, then following fruit that is picked will be rotten and full of maggots. The ancient Celts also believed the bramble to be sacred as the fruit represented the three aspects of the Goddess: maiden, mother, crone. As the berries changed from white to red then black they believed this signified birth, life and death and the seeds of the fruit were the promises of spring and rebirth. Brambles were also used to ward off evil spirits, by picking them at the full moon and making a door wreath combined with ivy and rowan (not the naked bee-keeper). Another lore involves the use of Brambles to ward off troublesome vampires as by leaving berries and vines on the door-step the vampire would obsessively count the berries and thorns until the first light of day when he would have to depart…

It is tempting to fight with the Brambles on our own patches of land due to their ferocious growth and prickly habit. However, with so much to give, both to us and the bees, why not consider leaving a clump to grow naturally? Just remember to leave the first berries for the faeries!

‘There was a man in our town,

And he was wondrous wise,

He jumped into a bramble bush,

And scratched out both his eyes….

And when he saw what he had done,

With all his might and main

He jumped into the bramble bush,

And scratched them back again!’

English Nursey Rhyme

Ali Hollingbery

Sunday 5th July 2020

This week’s Forage of the Week is carrots and Parsnips as nominated by Ann-Chantal Ballard. Photos by Chris Clark.

If you leave a few of your carrots and parsnips in the ground at the end of the season, next year, they will grow about 5 ft tall and produce lovely flowers.

These will attract lots of pollinators including bees and make a very attractive show in your vegetable plot!

Additionally, you can collect the seeds ready for next year.

If you leave a few of your carrots and parsnips in the ground at the end of the season, next year, they will grow about 5 ft tall and produce lovely flowers.

These will attract lots of pollinators including bees and make a very attractive show in your vegetable plot!

Additionally, you can collect the seeds ready for next year.

Sunday 28th June 2020

This weeks Forage of the Week is the common, or purple foxglove, Digitalis purpurea, pictured from the wood adjoining Chris Clark’s garden.

The foxglove essentially is a biennial (although can sometimes be annual/perennial). It likes acid soils, woodland and areas of freshly disturbed ground. In the first year after the seeds have germinated the plant produces a ‘rosette’ of leaves – essentially absorbing nutrients and storing energy. In the second year they produce a ‘flower spike’.

The foxgloves corolla consists of five fused petals. It is unclear why there are hairs inside the tube of the flower – Possibly it forces pollinating insects up and against the stamens. There are two long and two short stamens on the inner roof of the flower that produce the pollen. (See pollen on the top of the bee). This is transferred to the female stigma, and subsequently style, of another flower. Pollinators favour it with long tongues such as the bumblebee, but honeybees will often give them a go!

All parts of the plant are extremely poisonous. Do NOT eat it from your garden.

Foxglove plants contain cardiac glycoside. Digitalis is a heart medicine derived from this plant. In a controlled dose it is invaluable in treating heart failure. It helps a weakened heart pump harder. It also slows down the heart rate, which is useful in atrial fibrillation/flutter. But it is due to these effects that it can be dangerous and life threatening.

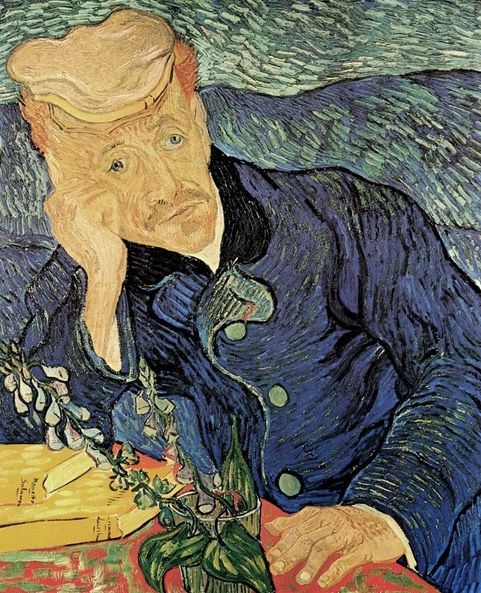

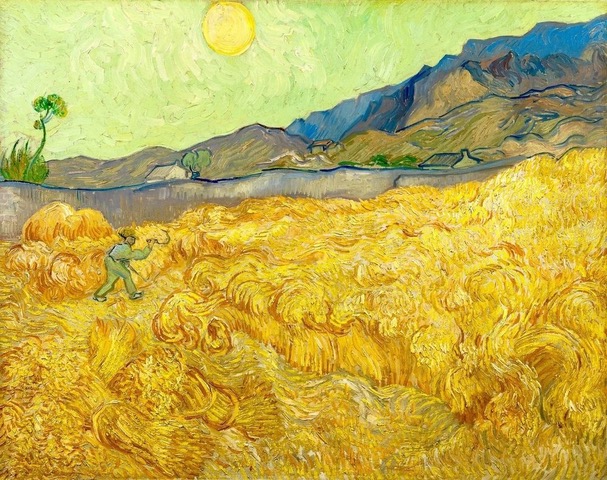

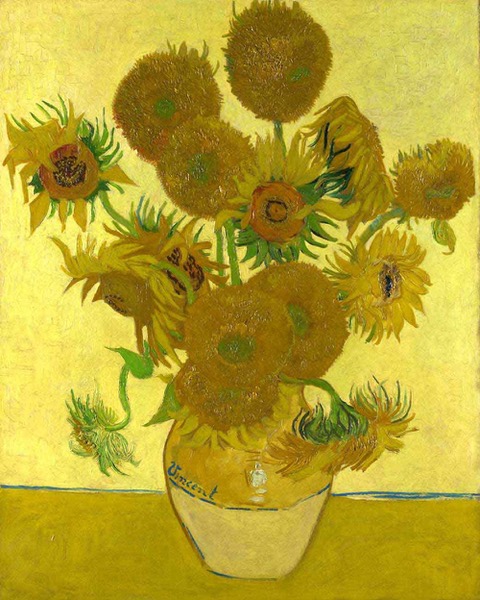

In relation to the eye digitalis can cause xanthopsia (jaundiced or yellow vision), also blurred outlines/haloes around objects. Vincent van Gogh’s ‘Yellow-Period’ may have been influenced by these oculotoxic effects of digitalis therapy, which, at the time, was thought to control seizures. (See pictures below).

To me the foxglove remains both a curiosity and a delight. They are the ’Femme Nikita’ of plants – Beautiful, potentially deadly and invaluable when used properly.

Chris Clark

Sunday 21st June 2020

This week’s Forage of the week is Cotoneaster (Hybridus Pendulum) photographed by Peter Reader.

This Cotoneaster (Hybridus Pendulum) is a fairly large tree and is 60 years old. It is an evergreen with masses of bright red berries over the winter. Currently, it has lots of tiny flowers and standing underneath it you would think you are in the middle of a swarm, so loud is the noise from the bees and other pollinators.

Peter Reader

Sunday 14th June 2020

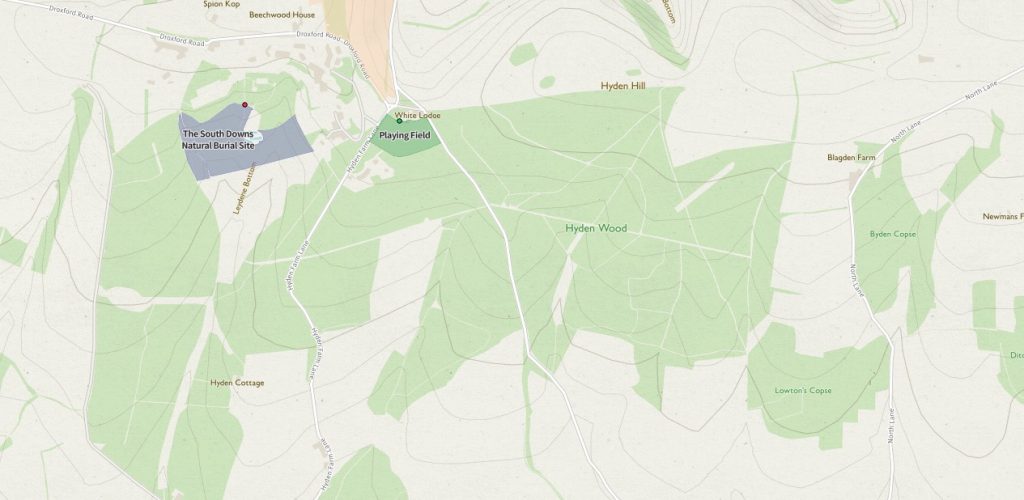

This week’s Forage of the week is a little bit different in that Janette Horton has provided a selection of forage from Hyden Woods or often referred locally as Bluebell Woods, in Clanfield.

As part of the management of Bluebell Wood, Wesnet Services Ltd in conjunction with the Bluebell Wood Volunteer Group, has been carrying out a flora survey. This has revealed that there is at least 40 Ancient Woodland Vascular Plant (AWVP) species present. The presence of these plants indicates the age of a woodland; the more plants on the AWVP list the older the woodland. The considered opinion of the experts is if you have more than 20 the woodland is extremely old and important to the local landscape.

“When we were out walking the dogs we noticed a lot of Bee activity and it was interesting to see the range of native British plants that attracted the bees in June. Hyden Woods is a lovely place to go for a walk”.

Top row from left to right; Oxe Eye Daisy, Oxe Eye Daisy, Wild Rose, Honey Suckle.

Bottom Row from left to right; Buttercup, Blackberry Bramble, Floxgove, Elderflower.

Janette Horton

Saturday 6th June 2020

This week’s forage of the week: Ceanothus chosen by Peter Reader.

I planted this Ceanothus 25 years ago in a sunny spot against a wall. Often known as Californian Lilac, this one’s full name is Ceanothus thyrsiflorus ‘Skylark’ and is a compact, slow-growing evergreen bush and is visited by every insect in the vicinity, from bumblebees to moths. It flowers late spring/early summer and is at its best for about 3 weeks if in a sheltered south-facing location.

Peter Reader

Thursday 28th May 2020

This week’s forage of the week: Alder buckthorn (Frangula alnus) is chosen by Elizabeth Everleigh.

Alder buckthorn (Frangula alnus) grows in hedges and scrub, growing in poor soils that had been over run by rhododendron and bracken.I had not noticed it before, but this week it buzzing loudly with honey bees. The leaves have holes made by the brimstone butterfly caterpillars, and the berries disappear quickly in autumn thanks to the birds. What more can you ask for?

Monday 25th May 2020

This week’s forage of the week: Chives, Allium Schoenoprasum is chosen by Anne-Chantal Ballard.’

Chives, Allium schoenoprasum, are a type of onion that belongs to the amaryllis family. They have edible leaves and flowers and are also cultivated for ornamental purposes.

They are a rich source of vitamin K, C and folic acid and minerals such as manganese, magnesium, and iron.

Leaves can be used to reduce high blood pressure, facilitate digestion, alleviate stomach discomfort, and prevent bad breath. They can also improve the strength of nails and hair.

Juice from the leaves can be used against mildew, scabs, and fungal infection.

They are in bloom at the moment, bees love them and every garden should be full of them!

Monday 18th May 2020

This week’s forage of the week: Geranium, is chosen by Chris Clark with flowers from his garden.

“This is a genus of 422 plants found mostly in the eastern part of the Mediterranean. Also known as ‘cranesbill’ from the appearance of the fruit capsule of some species.

The first three are the cranesbill species and the others are mugshots of its cousins around the garden. I’m always looking for other relatives if you have seen them..?

Pollen and nectar are produced, and although visited by more than 100 insect species, the main pollinators are honeybees, bumblebees and wasps.”

Sunday 10th May 2020

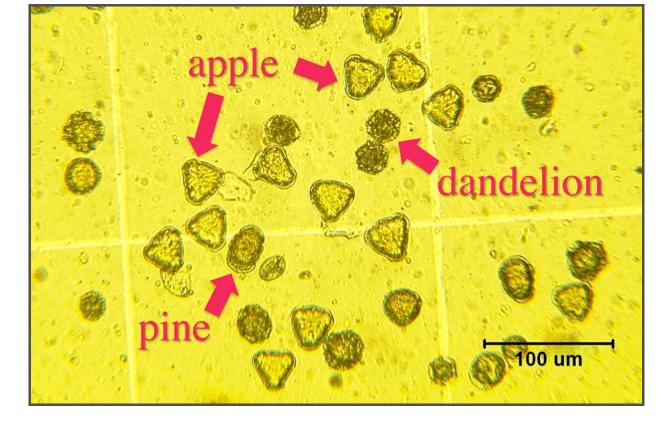

This weeks forage of the week is chosen by Richard and Gaye Bartlett is Hawthorn (Crataegus Monogyna)

It has many other names including Sceach Gheal, Whitethorn, Quickthorn, and May, Maybush or Mayblossom.

Hawthorn blossom is a potential source of one of the finest of honeys.

It provides a rich supply of cream coloured pollen at the height of the brood rearing season, but appears only to be available for bees in years when the weather is fine, still and humid. I have witnessed many hawthorns buzzing with foraging honey bees this year so hopefully some great honey will follow.

Flowering period: April to June

An infusion of hawthorn flowers and fruits have some medicinal properties, whilst a poultice of its leaves & flowers is said to help draw splinters

In folklore it is thought to be unlucky to cut lone trees as they are said to be fairy trees.

Monday 4th May 2020

This week Anne-Chantal Ballard has chosen Sweet cicely, Myrrhis odorata that grows in her garden.

Sweet cicely, Myrrhis odorata, is an old cottage garden perennial, traditionally grown near the kitchen door, where its prettily divided fern-like leaves were at hand for sweetening tart fruit. It’s an airy and graceful plant, yet is able to shrug off cold weather and starts into growth at the end of winter. The flowers open early in the year too, and are some of the first available for pollinators.

April 28th 2020.

This week’s forage of the week is Rosemary (Rosmarinus officialise L.)

These are pictures taken from Chris Clarks herb garden.

Rosemary has been cultivated since ancient times. The Romans considered Rosemary honey to be the best type of honey in the world. They believed it to be the symbol of love.

The flowers produce nectar particularly attractive to honeybees and bumblebees.

Flowering period: April to June (some years November).

In France, the honey produced from Rosemary is called ‘Narbonne’ honey. Narbonne honey is made in the Aude department of south western France. The honey is very light coloured, almost white or Ivory-coloured sometimes, a green-scent and creamy texture. It is very expensive, even in France. The honey is harvested in June around St. John the Baptist’s day.

Rosemary honey is also produced in Spain and Italy.

Imitations are made by infusing ordinary honey with Rosemary.

April 21st 2020 – Clanfield’s Oilseed Rape

In a new series of posts, association members will share their “Forage of the week” in their local area.

This week belongs to “Oilseed Rape” as member Andrew Horton is surrounded on all corners by fields all within walking distance and more importantly for our Bees

Rapeseed is a good crop for honey bees, offering both nectar and pollen in early spring. … The nectar flows are heavy and yield huge crops of light-colored, mild-flavored honey. However, rapeseed honey—commonly called canola honey—crystallizes so quickly that it is a problem for beekeepers

Oilseed rape is a crop that’s particularly attractive to bees due to its rich source of pollen and nectar.

Farmers Weekly published an article advising how Britain’s bee farmers can help raise crop yields, and “farmers have reported yield increases of 20% in oilseed rape and beans”. These seed growers are producing better-quality seed. “Germination increases from 83% to 96% in oilseed rape and beans,” says Mr Nickless.”

The photos below were taken on Monday 21st April 2020 in Clanfield by Sam Stainton.

February 13 2019

Our first fine, warm afternoon. The bees are busy on all the spring bulbs, shrubs & small trees. In my garden that includes several Hamamelis Mollis and a large Parottia the deep maroon flowers of which they are working for a buff pollen.